In late 2016, writer and author Kasey Edwards reached out to me and asked: Should parents get involved in their kids’ friendships? As she detailed in her article that published in The Sydney Morning Herald, my answer was simple: No.

As I said to Kasey, the message that we want to give our children is, “You’ve got this!” not, “Don’t worry, I’ve got this for you!”

Try thinking of yourself as a “Friendship Coach.” Coaches don’t go out there and play the game for their players. Instead, they give them advice and send them to play. Then, they stand back on the sidelines and watch. When they call their team in, they point out what they saw and give the players some tips and guidance. It should work that way with parents too, coaching your children through their friendships.

Here’s how Kasey so eloquently put it:

Rather than acting as lead negotiator in our children’s relationships, we should support them and coach from the sidelines with the following Dos and Don’ts:

Reframe friendship altercations as opportunities to learn valuable skills

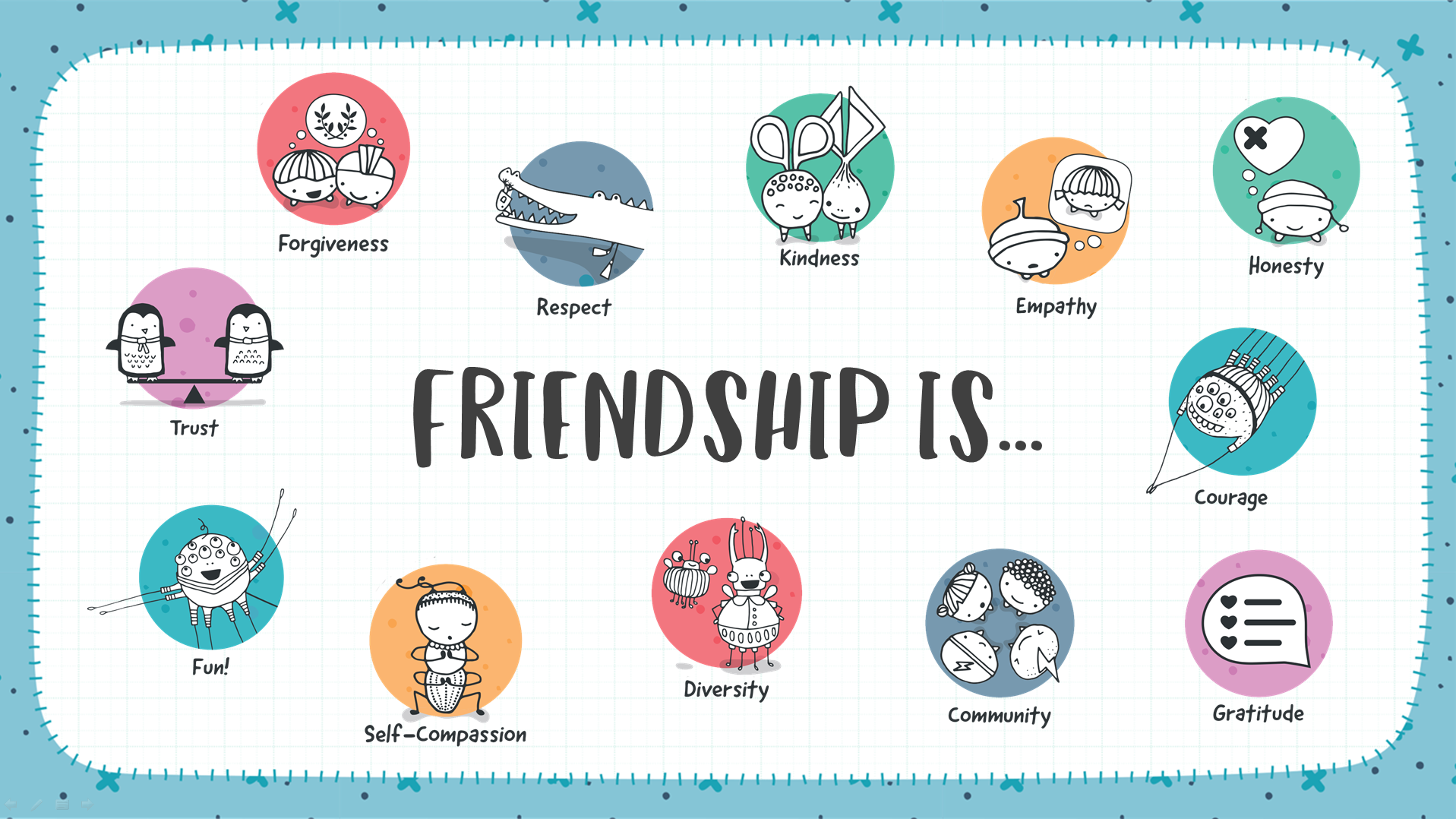

Research shows that children who have good social skills grow up to be more functional and successful adults. And the good news is that these skills can be taught.

“Like all skills, social skills take practice and don’t come naturally to all children,” says Kerford.

When our children are experiencing friendship problems it’s an opportunity for us to help them learn vital social skills, build resilience and strengthen their empathy.

Listen and empathise

While listening seems so simple, it’s probably often overlooked for that very reason. Just like adults, when kids talk about their problems they want to feel heard, validated and understood.

Kerford says that we need to remind ourselves that what might seem small to an adult can loom large in the eyes of a child; so large that it can seem overwhelming.

“Tune in and ask direct, specific questions,” says Kerford. “Often children have a hard time articulating what’s going on, they just ‘feel bad’. Help them put a voice to it by digging deeper.”

Encourage kids to stand up for themselves

When my daughter talks to me about her friendship problems, my default response is to say to her the things that were said to me. “Just ignore him”, “Walk away”, “She’s just jealous” are the kinds of phrases that instantly spring to mind.

But Kerford says that these responses can be too passive and minimising. She suggests taking some time to listen and empathise — and then follow up by asking “Did you stand up for yourself?”

Rather than retreating, we should encourage our kids to confront their problems and not simply put up with bad behaviour.

Kerford suggests asking kids what they could do differently next time and role-play different scenarios so they feel practised and more confident.

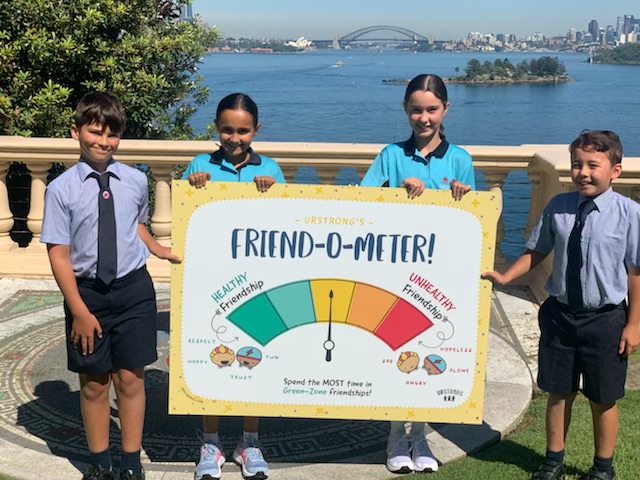

Teach kids the difference between healthy and unhealthy friendships

This one is the sort of advice that will be useful right into adulthood.

It’s important for our kids to know that they are in control of their lives. Kerford says that this includes the people they choose to surround themselves with. Do their friends make them feel good about themselves? If not, they should minimise the time they spend with people who make them feel bad and spend most of their time with friends who treat them well.

“Let them know that trust and respect are ‘must haves’ when it comes to friendship,” Kerford says. “Don’t say, ‘This is just something all girls must go through.’ This statement tells a girl she must suffer through and she is helpless. We cannot normalise the behaviours of ‘mean girls’.”

What about bullies?

There’s a lot of talk about bullies and bullying at the moment. But Kerford’s advice is to avoid the word altogether. The reason is that it’s often misused and leads children — and their parents — to label kids. Instead, she suggests the term “mean-on-purpose”.

“Children understand what this means and know when someone is intentionally trying to hurt them.”

Parents can help their kids come up with a quick comeback statement to combat mean-on-purpose behaviour. It doesn’t have to be an Oscar Wildean witticism. A simple “Not cool”, “Wow” or “That was really mean” will suffice.

Quick comeback statements should be delivered in a strong voice with authoritative body language, and then the child should walk away.

“If they’ve tried using a quick comeback and the person continues to be mean-on- purpose, that’s when an adult needs to get involved,” says Kerford. “It’s the responsibility of the adults (parents and teachers) to ensure that children feel safe and supported.”

Be a good role model

Anyone who’s sworn their head off during a spot of road rage only to have their little darling repeat it the next day at Grandma’s house knows our kids are watching us and modelling our behaviour. Especially, it seems, the bad bits.

“I know it’s so much pressure on parents, but their children are watching them and mirror their behaviour. If we don’t want our child to gossip, we don’t gossip” says Kerford. “If we don’t want our child to yell, we don’t yell. It’s as simple as this: If you want your child to be kind, show them what being kind looks like.”

Tell stories

Sometimes our kids forget that we were once kids too. Providing examples from our own life experience or of other people overcoming similar difficulties can help guide kids to a solution.

“Sharing your stories about some of the ups and downs you experienced in friendships when you were their age helps your child view you as not just mum or dad, but as someone who’s been there before,” Kerford says.

Kasey Edwards is a writer and best-selling author. www.kaseyedwards.com

Join our Community!

To help you begin on your “Friendship Coaching” journey, check out this Language of Friendship course that is part of our FREE URSTRONG Family Membership. The series consists of 10 videos designed to watch alongside your child to help you learn easy-to-use language & strategies to talk about tricky friendship issues.

Written by Dana Kerford

Friendship Expert and Founder of URSTRONG